“No Tree—No Leaf”: Applying Resilience Theory to Eucalypt-Derived Musical Traditions

Robin Ryan

pages 57-68

TABLE 1: EUCALYPTUS AS MUSICAL RESOURCE

© Robin Ryan, 2014

NOTE: Earlier didjeridus may have been made from Bamboo (Bambusa arhemica).

Popular Gumleaf Music Species

Yellow Box (E. melliodora; called ‘Stradileaf’ by competitive leafists at Maryborough, Victoria)

Red Ironbark (E. sideroxylon; local name Mugga; played by Philip Elwood in Melbourne, Victoria)

River Red Gum (E. camaldulensis; leaf soundmaker of the Yorta Yorta, Victoria)

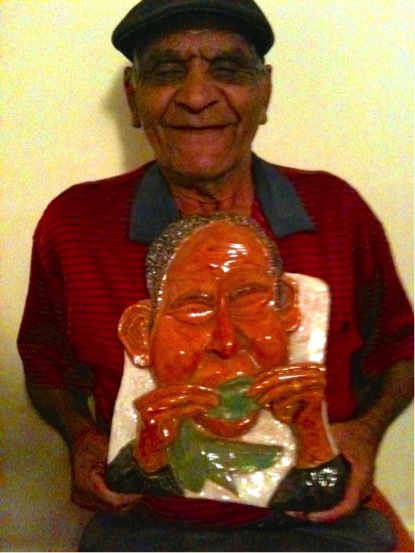

Forest Red Gum (E. tereticornis; ‘music tree’ grown by Uncle Herb Patten in Melbourne, Victoria)

Red Box (E. polyanthemos; played by Will Lockwood in northern Victoria)

Candlebark (E. rubida; played by Wendy Eva in northern Victoria)

White Stringybark (E. globoidea; played by Lake Tyers Gumleaf Band in Gippsland, Victoria)

Gippsland Mahogany (E. botryoides, played by Lake Tyers Gumleaf Band in Gippsland, Victoria)

Coolabah; Coolibah (E. microtheca; played in Channel Country, SW Queensland)

Sydney Blue Gum (E. saligna; played by Aborigines at La Perouse, New South Wales)

Red-flowering Gum (E. ficifolia; played by Keith Lethbridge, Western Australia)

Popular Didjeridu Species

Darwin Stringybark (E. tetrodonta; local name Gadayka in the Dhuwa moiety, Northern Territory)

Darwin Woollybutt (E. minata; Gulngurru or Gungurru in the Yirritja moiety, Northern Territory)

Yellow Box (E. phoenicia; called Scarlet Gum by the Mayali of Katherine, Northern Territory)

River Red Gum (E. camaldulensis; supplies didjeridus in Northern Territory and Murray River, Victoria)

Bloodwood (Corymbia polycarpa, local name Badawil in Northern Territory)

Bloodwood (Corymbia ferruginea)

Rough-barked Gum (E. ferruginea; local name Aiyangbarda on Groote Eylandt, Northern Territory)

Swamp Bloodwood (Corymbia ptychocarpa; supplies yigi-yigi, Cape York Peninsula, Queensland)

Mallee Didjeridu Species: (examples found in Western Australia Goldfields)

Silver Mallee (E. crucis)

Red Mallee (E. Oleosa)

TABLE 2: THE EUCALYPT MUSIC-CULTURES COMPARED

© Robin Ryan, 2014

[table id=1 /]

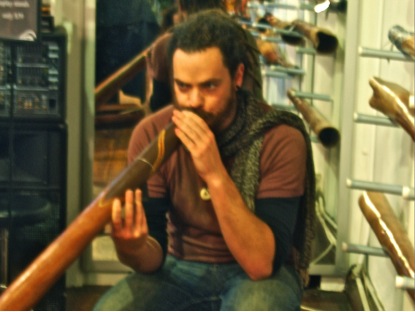

FIGURE 1: Tim O’Farrell performs at Didgeridoo Breath, Fremantle, WA. Image by Robin Ryan, 2012, courtesy Tim O’Farrell and Sanshi

FIGURE 2: Leaf player and Gunai-Kurnai Elder Uncle Herb Patten with his sculptured self-portrait. Image by Robin Ryan, 2014, courtesy Herb Patten.

FIGURE 3: Potential musical instruments at Dubbo, New South Wales. Image by Robin Ryan, 2012.

FIGURE 4: Leaf Instruments of Red-Flowering Gum (Eucalyptus ficifolia), Perth, WA. Image by Robin Ryan, 2005.

FIGURE 5: Stringybark Eucalyptus tree at Bathurst, New South Wales. Image by Robin Ryan, 2012.

VIDEO LINKS FOR GUMLEAF MUSIC:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpWUEEuXBtg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHo7XUeiUwg

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY.

Allen, Aaron S. 2013. “Environmental Changes and Music.” In Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories that Shaped our Culture, edited by Jacqueline Edmondson, 417-421. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood.

Allen, Aaron S., Kevin N. Dawe, and Jennifer C. Post. Forthcoming. The Tree That Became a Lute: Musical Instruments, Sustainability and the Politics of Resource Use. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Atherton, Michael. Australian Made… Australian Played: Handcrafted Musical Instruments from Didjeridu to Synthesiser.1990. Kensington, NSW: NSW University Press.

Australian National Botanic Gardens. 2012. “About Eucalypts.” Euclid. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cpbr/cdkeys/Euclid/sample/html/learn.htm#inspection.

Gammage, Bill. 2011. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin.

Hughes, Lesley, E.M. Cawsey and Mark Westoby. 1996. “Climatic Range Sizes of Eucalyptus Species in Relation to Future Climate Change.” Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters 5/1: 23-29.

Jones, Trevor. 1967. “The Didjeridu: Some Comparisons of its Typology and Musical Functions with Similar Instruments Throughout the World.” Studies in Music 1: 23-55.

Kartomi, Margaret J., Robin Ryan, and Darren Williams. 1995. “Didjeridu.” In Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG) II, revised edition, edited by Ludwig Finscher, 1234-1240. Kassel: Barenreiter-Verlag.

Lindenmayer, David B. and Joern Fischer. 2006. Habitat Fragmentation and Landscape Change: An Ecological and Conservation Synthesis. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing.

Lindner, David, ed. 2004. The Didgeridoo Phenomenon from Ancient Times to the Modern Age. Schönau, Germany: Traumzeit Verlag.

Moyle, Alice. 1981. “The Australian Didjeridu: A Late Musical Intrusion.” World Archaeology 12/3: 321–31.

Neuenfeldt, Karl, ed. 1997. The Didjeridu – From Arnhem Land to Internet. Sydney: John Libbey/Perfect Beat.

Patten, Herbert. 1999. How to Play the Gumleaf (CD with accompanying booklet). Sydney: Currency Press.

Ryan, Robin. 2003. “Jamming on the Gumleaves in the Bush ‘Down Under’: Black Tradition, White Novelty?” Popular Music and Society 26/3 (October), Special Issue: Reading the Instrument, guest edited by Steve Waksman, 285-304. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Walker, Brian, and Jacqueline A. Meyers. 2004. “Thresholds in Ecological and Social-Ecological Systems: A Developing Database.” Ecology and Society 9/2.

Woinarski, J.C.Z. and J. Westaway. 2008. “Hollow formation in the Eucalyptus miniata – E. tetrodonta open forests and savanna woodlands of tropical northern Australia.” Final report to Land and Water Australia (Native Vegetation Program). Project TRC-14. http://www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/bitstream/handle/10070/222493/2008_Woinarski_J.C.Z._and_Westaway_J.pdf?sequence=1.